We were now one day closer to our boat trip. The boat trip, however, departed from Seward, so this day was all about driving from point A (Anchorage) to point C (Seward) with a short side trip to point B (Portage Lake).

View Larger Map

This drive took us past Turnagain Arm (again). Since it was another mostly cloudy day, and the tide was out, it looked the same this day as it had on our previous visit.

My previous post of the horse shaped iceberg (or is it dragon shaped?) was from the short side trip to Portage Lake. Here is a wide-angle view of Portage Lake, taken from the Begich, Boggs Visitor Center. The distant glacier in this photo (middle left) is actually Burns Glacier, not Portage Glacier. About a hundred years ago, Burns Glacier flowed into Portage Glacier, and Portage Glacier terminated close to where this picture was taken. Since then, Portage Glacier has receded considerably (nearly 5km), exposing Portage Lake along the way. It has, however, been fairly stable since 1999. While the retreat of Portage Glacier was helped by a warming climate, the main driver was the transition from a land-based terminus to a water-based terminus. Said another way, glacier ice calves more frequently in water than on land. You can read a more thorough history (and see historical photos) here.

We also stopped to experience the quiet beauty of a lake with views of Explorer Glacier. We could have sat here for hours, but lack of food and the desire to arrive in Seward urged us onward.

After our little side trip to Portage Lake, we got back onto the main road heading south towards Seward. Soon after that we discovered the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center (AWCC). They are a non-profit that takes in injured and orphaned animals. Those that cannot be released back into the wild are given a home on the AWCC property. You can drive or walk through and see Moose, Elk, Black Bear, Grizzly Bear, and a few others.

I am glad that there is a group like the AWCC to care for these animals. I suspect that without the AWCC, these animals would not be alive. But seeing wild animals kept behind fences has always been a bittersweet experience for me. As much space as the AWCC provides these animals, they are still stuck behind a fence. Ah...if only the world was the perfect place I wished it would be ;-)

The resident Moose seemed very used to humans. They would saunter up to the fence even when people were nearby. We got a nice face-to-face encounter with a Moose.

Other than good judgment (and a dose of fear), there was nothing preventing me from reaching through the fence to touch this really large animal. I saw some others doing that very thing later in our visit, but that fence did not seem to really provide much of a barrier. Moose are BIG, and they have pointy antlers.

What Do You See?

So...obviously this is a chunk of ice floating in a pond. An iceberg that calved off of Portage Glacier. I really do not have a lot of experience with icebergs, but I think that they might be a little bit like clouds. Sometimes you look at them and you can see certain shapes or scenes.

When I looked at this particular iceberg, I imagined a frozen horse swimming through the water. Only his head is above the water, a bit of frozen breath puffing from his nostrils (or maybe he is sticking his tongue out :-), and a wave of frozen water splashing up behind him. Is it just me? Hint: he is swimming to the left.

When I looked at this particular iceberg, I imagined a frozen horse swimming through the water. Only his head is above the water, a bit of frozen breath puffing from his nostrils (or maybe he is sticking his tongue out :-), and a wave of frozen water splashing up behind him. Is it just me? Hint: he is swimming to the left.

Hatcher Pass

We were both already thinking about the boat trip we had booked in Seward. We were excited about the possibility of seeing whales, and puffins, and glaciers and, and...

But we had to wait. It was like Christmas. There was this shiny gift under the tree, but we had to wait two more days to open it. So, on our second day in Anchorage we considered our options and ultimately decided to visit Hatcher Pass. This was not something we had planned to do months in advance, but something decided the night before. We had mulled through a list of things that caught our attention and somehow ended up with Hatcher Pass. I am not sure at all what it was that led to that decision, but that is where we ended up going. It was nice being flexible and making "game time decisions", but that approach also has some downside to it. More about that below.

View Larger Map

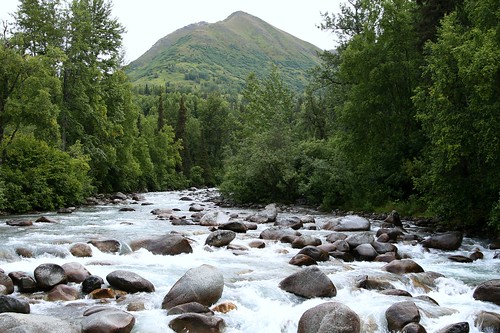

Hatcher Pass is located in the Talkeetna Mountains, north of Anchorage. As you enter the Talkeetna Mountains, the road begins to parallel the Little Susitna River (not to be confused with the "regular" Susitna River, a bit farther to the west) as it tumbles down to Cook Inlet. We took advantage of the scenic opportunities with the river that were provided to us.

Eventually you turn off the paved road onto a gravel and packed dirt road. This is the road that actually takes you through Hatcher Pass. It isn't maintained once the snow starts falling, and thus usually gets closed in late September until the following June or July. There were lots of potholes, which made for quite the bumpy ride.

Hatcher Pass was beautiful. The views were stunning (even on a cloudy day). When we got out of our car and just listened, the silence was amazing. The only thing I heard was the hum of my aging ears. No cars, planes, music, or other people. Every now and then we would hear some animal or bird, but otherwise this place has become my new standard for "quiet".

We got out of the car to explore a couple of times, but unfortunately we were not prepared for much more than that. Had we done more research, we would have known that there are several hiking trails located at Hatcher Pass, that took you up a little higher on the mountains next to the dirt road. These were easy hikes that, out of ignorance, we simply had not prepared for. We would have definitely taken the time to explore those trails had we known. Without exploring the trails, I still found it difficult to pull myself and my camera away from the views and the carpet of lush growth on the mountain sides.

Just beyond Hatcher Pass you come to tiny Summit Lake. We explored here and tried to capture the quiet beauty of this lake with our cameras.

While we explored, the quiet was interrupted fairly regularly by nearby critters. There was some type of varmit hanging out on nearby rocks, making this squeaking noise. Varmit, of course, is technical jargon for something that looked like a marmot or ground squirrel. It had four short legs, was furry all over, made me think of Ewoks, looked like it might be willing to take food from a human, and seemed to call an underground burrow its home. And it was squeaky.

Then there were the Ptarmigans. On the rocky side of the mountain above us there was a flock of Ptarmigans. They were fluttering about, moving from roost to roost, making all kinds of interesting noises. The noise that was the most memorable to me was a frog like groan sound. I have not been able to find a recording on the web that matches the sound I remember (which is more likely a factor of my memory than the recordings on the web). I had my binoculars with me, but my scope sat back in the hotel room (sigh). Beyond the fact that I was seeing and hearing some type of Ptarmigan, I was unable to conclusively identify them as one of the three Ptarmigans that occur in North America (Rock, White-tailed or Willow...that sound I remember seems to be closest to White-tailed). Any of them would have been a lifer for me. Another example of where some more planning might have saved me some frustration.

Never mind that. Look at the beautiful views!

The ride down the opposite side of Hatcher Pass continued to be very scenic. To a point. Somewhere in the drive down to Willow it turned from scenic Alaskan valley into a very bumpy, pothole filled drive through a forest.

Hopefully this post did not come across too negatively. I am absolutely happy we visited Hatcher Pass, even with some of the frustrations. It is one of the most beautiful places that I have ever seen. On some future trip to Alaska, if I had the chance to visit Hatcher Pass again, I would come better prepared: plan to hike, plan to bird watch and don't bother driving down the far side of Hatcher Pass to Willow (just turn around at Summit Lake).

But we had to wait. It was like Christmas. There was this shiny gift under the tree, but we had to wait two more days to open it. So, on our second day in Anchorage we considered our options and ultimately decided to visit Hatcher Pass. This was not something we had planned to do months in advance, but something decided the night before. We had mulled through a list of things that caught our attention and somehow ended up with Hatcher Pass. I am not sure at all what it was that led to that decision, but that is where we ended up going. It was nice being flexible and making "game time decisions", but that approach also has some downside to it. More about that below.

View Larger Map

Hatcher Pass is located in the Talkeetna Mountains, north of Anchorage. As you enter the Talkeetna Mountains, the road begins to parallel the Little Susitna River (not to be confused with the "regular" Susitna River, a bit farther to the west) as it tumbles down to Cook Inlet. We took advantage of the scenic opportunities with the river that were provided to us.

Eventually you turn off the paved road onto a gravel and packed dirt road. This is the road that actually takes you through Hatcher Pass. It isn't maintained once the snow starts falling, and thus usually gets closed in late September until the following June or July. There were lots of potholes, which made for quite the bumpy ride.

Hatcher Pass was beautiful. The views were stunning (even on a cloudy day). When we got out of our car and just listened, the silence was amazing. The only thing I heard was the hum of my aging ears. No cars, planes, music, or other people. Every now and then we would hear some animal or bird, but otherwise this place has become my new standard for "quiet".

We got out of the car to explore a couple of times, but unfortunately we were not prepared for much more than that. Had we done more research, we would have known that there are several hiking trails located at Hatcher Pass, that took you up a little higher on the mountains next to the dirt road. These were easy hikes that, out of ignorance, we simply had not prepared for. We would have definitely taken the time to explore those trails had we known. Without exploring the trails, I still found it difficult to pull myself and my camera away from the views and the carpet of lush growth on the mountain sides.

Just beyond Hatcher Pass you come to tiny Summit Lake. We explored here and tried to capture the quiet beauty of this lake with our cameras.

While we explored, the quiet was interrupted fairly regularly by nearby critters. There was some type of varmit hanging out on nearby rocks, making this squeaking noise. Varmit, of course, is technical jargon for something that looked like a marmot or ground squirrel. It had four short legs, was furry all over, made me think of Ewoks, looked like it might be willing to take food from a human, and seemed to call an underground burrow its home. And it was squeaky.

Then there were the Ptarmigans. On the rocky side of the mountain above us there was a flock of Ptarmigans. They were fluttering about, moving from roost to roost, making all kinds of interesting noises. The noise that was the most memorable to me was a frog like groan sound. I have not been able to find a recording on the web that matches the sound I remember (which is more likely a factor of my memory than the recordings on the web). I had my binoculars with me, but my scope sat back in the hotel room (sigh). Beyond the fact that I was seeing and hearing some type of Ptarmigan, I was unable to conclusively identify them as one of the three Ptarmigans that occur in North America (Rock, White-tailed or Willow...that sound I remember seems to be closest to White-tailed). Any of them would have been a lifer for me. Another example of where some more planning might have saved me some frustration.

Never mind that. Look at the beautiful views!

The ride down the opposite side of Hatcher Pass continued to be very scenic. To a point. Somewhere in the drive down to Willow it turned from scenic Alaskan valley into a very bumpy, pothole filled drive through a forest.

Hopefully this post did not come across too negatively. I am absolutely happy we visited Hatcher Pass, even with some of the frustrations. It is one of the most beautiful places that I have ever seen. On some future trip to Alaska, if I had the chance to visit Hatcher Pass again, I would come better prepared: plan to hike, plan to bird watch and don't bother driving down the far side of Hatcher Pass to Willow (just turn around at Summit Lake).

Black-billed Magpie

Black-billed Magpies were everywhere. They scolded us on the quiet side of Potter Marsh, and harassed a Merlin on the boardwalk side of Potter Marsh. They were poking around the dumpsters at the fast food restaurants, and squawking in the trees within Anchorage. They have obviously adapted to the urban areas of Anchorage, and its surrounding sprawl.

On our second day in Alaska we decided to drive up to Hatcher Pass. On the way up to the pass, within the Talkeetna Mountains, there was a small gravel pull-out on the side of the road. We pulled over onto the gravel in order to take some photos of the view. As soon as the car pulled off the road, right on cue, a Black-billed Magpie hopped out of the nearby underbrush and joined us on the gravel. I had this feeling that the bird associated easy food with cars and people, but I have no way of proving that. Instead of giving him food, I took his picture.

On our second day in Alaska we decided to drive up to Hatcher Pass. On the way up to the pass, within the Talkeetna Mountains, there was a small gravel pull-out on the side of the road. We pulled over onto the gravel in order to take some photos of the view. As soon as the car pulled off the road, right on cue, a Black-billed Magpie hopped out of the nearby underbrush and joined us on the gravel. I had this feeling that the bird associated easy food with cars and people, but I have no way of proving that. Instead of giving him food, I took his picture.

Flattop Mountain

Before we departed for Alaska, we did some research into possible day hikes. I found that one of the most popular hikes in the Anchorage area is Flattop Mountain. It is only about 3 miles long, so I was not expecting it to be very demanding, and the panoramic views it offered were touted to be outstanding. It sounded like a winner.

In my research I found several descriptions of the hike on the web, but this one caught my attention. In particular, the summary mentioned "bad trail conditions at the top", "several potential hazards", "exercise extreme caution", "several hikers have been injured", and, my favorite, "novices may have problems". Hmmm...Wikipedia says that Flattop Mountain is the most climbed mountain in the entire state of Alaska. It seemed a bit ironic that such a popular trail would have so many warnings attached to it. Also, how do I know whether I am a novice or not? And a novice at what, exactly? Never mind that ominous trail description. After spending the first half of the day at Potter Marsh, we decided to give Flattop Mountain a try. How bad could it really be?

View Larger Map

The day had thus far been fairly cloudy. And when we got to the trail head we realized that we would have to contend with another issue: fog. It was like pea soup. Did that stop us? Ha! We ignored both the ominous trail description and the annoying fog. Onward!

So, up we went. As we approached the summit, the trail got steeper and steeper. And, the trail got less and less reliable. Lots of loose dirt and rock to consider, which required me to use my hands a lot more for balance and leverage. I would take a step, and then wait for my boot to stop sliding before taking the next step. And even though the fog was thick enough to prevent me from seeing any of the great views, I had this sense that any tumble would be a long tumble. It was when I found myself crawling up the side of the mountain (instead of walking...I think the correct term for this is "scrambling") because the angle of the trail was that steep, and the footing was that loose, that I reconsidered my interest in actually making it to the summit. Never mind the group of middle school aged kids who just bounded past us without any apparent concern, I was having second thoughts. I realized that I was perhaps a novice at whatever it was that this particular trail expected of its visitors. And because of the fog, there were no views. To me, the absence of views reduced the value of reaching the summit considerably.

We were within a few hundred yards of reaching the summit when we decided to reverse direction and head back down. That must have been an important decision, because about a third of the way down the mountain we noticed that the fog had finally begun to lift. I was a bit frustrated that I did not technically make it to the top of this mountain, but maybe we could get some nice views on the way down.

A view of the summit after the fog had lifted showed a rocky wonderland. If you stare at this photo hard enough, you can see a couple of successful scramblers taking in the now fog-free view from the advantage of the summit. They are the teeny, tiny little tip on that bump of rock in the middle of the summit.

Before we made it back to our car, the fog had completely evaporated, and the views came to life. On one side there were the Chugach Mountains. On the other was the sprawl of Anchorage.

While the fog was in place, it had washed away all the contrast and color. With the fog gone, however, clarity came to the small things too. I found this beauty next to the trail. It is called Alaskan Burnet.

And these young purplish cones are from Mountain Hemlock. I love the purple on green color combination.

In my research I found several descriptions of the hike on the web, but this one caught my attention. In particular, the summary mentioned "bad trail conditions at the top", "several potential hazards", "exercise extreme caution", "several hikers have been injured", and, my favorite, "novices may have problems". Hmmm...Wikipedia says that Flattop Mountain is the most climbed mountain in the entire state of Alaska. It seemed a bit ironic that such a popular trail would have so many warnings attached to it. Also, how do I know whether I am a novice or not? And a novice at what, exactly? Never mind that ominous trail description. After spending the first half of the day at Potter Marsh, we decided to give Flattop Mountain a try. How bad could it really be?

View Larger Map

The day had thus far been fairly cloudy. And when we got to the trail head we realized that we would have to contend with another issue: fog. It was like pea soup. Did that stop us? Ha! We ignored both the ominous trail description and the annoying fog. Onward!

So, up we went. As we approached the summit, the trail got steeper and steeper. And, the trail got less and less reliable. Lots of loose dirt and rock to consider, which required me to use my hands a lot more for balance and leverage. I would take a step, and then wait for my boot to stop sliding before taking the next step. And even though the fog was thick enough to prevent me from seeing any of the great views, I had this sense that any tumble would be a long tumble. It was when I found myself crawling up the side of the mountain (instead of walking...I think the correct term for this is "scrambling") because the angle of the trail was that steep, and the footing was that loose, that I reconsidered my interest in actually making it to the summit. Never mind the group of middle school aged kids who just bounded past us without any apparent concern, I was having second thoughts. I realized that I was perhaps a novice at whatever it was that this particular trail expected of its visitors. And because of the fog, there were no views. To me, the absence of views reduced the value of reaching the summit considerably.

We were within a few hundred yards of reaching the summit when we decided to reverse direction and head back down. That must have been an important decision, because about a third of the way down the mountain we noticed that the fog had finally begun to lift. I was a bit frustrated that I did not technically make it to the top of this mountain, but maybe we could get some nice views on the way down.

A view of the summit after the fog had lifted showed a rocky wonderland. If you stare at this photo hard enough, you can see a couple of successful scramblers taking in the now fog-free view from the advantage of the summit. They are the teeny, tiny little tip on that bump of rock in the middle of the summit.

Before we made it back to our car, the fog had completely evaporated, and the views came to life. On one side there were the Chugach Mountains. On the other was the sprawl of Anchorage.

While the fog was in place, it had washed away all the contrast and color. With the fog gone, however, clarity came to the small things too. I found this beauty next to the trail. It is called Alaskan Burnet.

And these young purplish cones are from Mountain Hemlock. I love the purple on green color combination.

Raptors

While Tammy and I explored Potter Marsh, we noticed two different raptors that appeared to have made the place their home: Northern Harrier and Merlin.

While driving from the opposite (non-birdy, very flowery, tick-infested) side of the marsh, we noticed a Northern Harrier perched on a post that was smack in the middle of the whole marsh. Several times after that, as we roamed about the boardwalk, we would see the flash of the Harrier's white rump as it cruised over the marsh looking for something tasty. I don't usually try to age birds, mainly because such efforts on my part usually end up in frustration, but my picture and the drawings for a juvenile Northern Harrier in Big Sibley seem to have a few things in common.

The other raptor was a small bird that I first identified as a Sharp-shinned Hawk. But I also knew that I was not super familiar with that species, so I asked another birder who was ahead of me on the boardwalk. Their answer was Merlin. Hmmm. At that point I had no photo because the bird was simply too far away. I made a mental note - that bird may be one that goes unidentified. It seemed, however, that this smallish raptor was "making the rounds", and it would reappear from time to time, usually being pursued by a self-appointed posse of Black-billed Magpies. When the bird decided to perch on an old root ball from some long toppled tree (still several yards away but now easily within the reach of my camera), I snapped a few photos in the hopes of ensuring that an identification could be made later. My review of the photo and a couple of field guides led me to conclude that it was indeed a Merlin. Here he is, fanning his tail, keeping an eye out for that posse I mentioned.

While driving from the opposite (non-birdy, very flowery, tick-infested) side of the marsh, we noticed a Northern Harrier perched on a post that was smack in the middle of the whole marsh. Several times after that, as we roamed about the boardwalk, we would see the flash of the Harrier's white rump as it cruised over the marsh looking for something tasty. I don't usually try to age birds, mainly because such efforts on my part usually end up in frustration, but my picture and the drawings for a juvenile Northern Harrier in Big Sibley seem to have a few things in common.

The other raptor was a small bird that I first identified as a Sharp-shinned Hawk. But I also knew that I was not super familiar with that species, so I asked another birder who was ahead of me on the boardwalk. Their answer was Merlin. Hmmm. At that point I had no photo because the bird was simply too far away. I made a mental note - that bird may be one that goes unidentified. It seemed, however, that this smallish raptor was "making the rounds", and it would reappear from time to time, usually being pursued by a self-appointed posse of Black-billed Magpies. When the bird decided to perch on an old root ball from some long toppled tree (still several yards away but now easily within the reach of my camera), I snapped a few photos in the hopes of ensuring that an identification could be made later. My review of the photo and a couple of field guides led me to conclude that it was indeed a Merlin. Here he is, fanning his tail, keeping an eye out for that posse I mentioned.

Yummy Fish For You!

When we visited the boardwalk within Potter Marsh, one of the first things we noticed was a Red-necked Grebe and its chick. They were swimming together when we first sighted them, but it didn't stay that way. Momma Grebe would occasionally swim off and then come back with a fish. I expected the chick to gobble down those fish pronto, but that was not the case. Two different times the chick had a nice yummy fish dangled under its beak and shoved into its face, but baby Grebe wasn't biting. This miniature pile of pictures tells the story. In the last picture, Momma Grebe is probably saying something like "Eat the damn fish!"

The missing picture is Momma Grebe giving up and eating the fish herself.

The missing picture is Momma Grebe giving up and eating the fish herself.

No Birds

The first place that we visited in Alaska was Potter Marsh, just south of Anchorage. Potter Marsh is an excellent location for bird watching, but we managed to find a corner of the marsh that was pretty darn quiet. We went first thing in the morning, and decided to first visit the east side, which is opposite from where the parking lot and boardwalk are located. On the east side, there is a small gravel lot, and you can really only walk up to the edge of the marsh. And that is just what we did.

After about twenty minutes, however, the only sign of a bird was a nearby Black-billed Magpie, apparently scolding us for daring to even exit our car in its presence. Since I knew we were still headed over to the parking lot and that boardwalk, I did not fret over the apparent lack of birds. Instead I turned my attention to some colorful plants that were next to the marsh.

First up is some type of grass. It caught my eye because of the purplish hue that it had, so I squatted down in order to frame it against something green. I have no idea what name to give this grass.

Next up is a wild flower with a couple of cool names: Yellow Toadflax or Butter-And-Eggs. Its flowers have a very interesting shape and color. I was disappointed, however, when I got home and tried to find a name for what I had photographed. A bit of research gave me the name, but also let me know that this cute thing is actually an invasive species in Alaska.

Last up is Fireweed. We saw plenty of this beautiful purple flower the entire week. I crawled around in the weeds and grass to get this photo, and managed to pick up a tick as well. Happily, I can report that this tick turned out to be my only insect encounter for the entire week. I came prepared for masses of mosquitoes, but I never even had to apply repellent. I think I got lucky.

After about twenty minutes, however, the only sign of a bird was a nearby Black-billed Magpie, apparently scolding us for daring to even exit our car in its presence. Since I knew we were still headed over to the parking lot and that boardwalk, I did not fret over the apparent lack of birds. Instead I turned my attention to some colorful plants that were next to the marsh.

First up is some type of grass. It caught my eye because of the purplish hue that it had, so I squatted down in order to frame it against something green. I have no idea what name to give this grass.

Next up is a wild flower with a couple of cool names: Yellow Toadflax or Butter-And-Eggs. Its flowers have a very interesting shape and color. I was disappointed, however, when I got home and tried to find a name for what I had photographed. A bit of research gave me the name, but also let me know that this cute thing is actually an invasive species in Alaska.

Last up is Fireweed. We saw plenty of this beautiful purple flower the entire week. I crawled around in the weeds and grass to get this photo, and managed to pick up a tick as well. Happily, I can report that this tick turned out to be my only insect encounter for the entire week. I came prepared for masses of mosquitoes, but I never even had to apply repellent. I think I got lucky.

Mostly Cloudy Mostly Mud

Our trip to Alaska is over. We did relax. We did see some wildlife. I even got some life birds. And I took a ton of pictures. Too many pictures. Well...not "too many", but nearly that many. The constraints of time and Internet bandwidth have prolonged my upload of pictures until tonight...the last day's photos are uploading to Flickr as I type. Since I am shy (or picky...you decide) these piles of uploaded photos are all marked private until I get a chance to look them over, pick out my favorites, clean them up "just so" and mark them public. Some of these public photos will eventually end up in a future blog post. I already know there will be cute large-billed birds and large swimming mammals, but I am still in the thrall of discovery at the moment.

All I have for this post are a couple of mostly cloudy pictures of Turnagain Arm. Mostly cloudy was what we had every day, except for the last two, and maybe an hour or two here and there on the other days. No complaints here about the weather - you do not go to Alaska for warm, sunny, predictable weather - but it did pose some interesting photographic challenges.

Turnagain Arm is not an anatomical reference. It is a body of water. If you come up the south edge of the Alaska Peninsula, the Pacific Ocean transitions into the Gulf of Alaska which in turn transitions into Cook Inlet (with the Kenai Peninsula on your right and Anchorage to the north and east). When Cook Inlet gets to Anchorage, the waterway splits - Knik Arm continues to the north of Anchorage, while Turnagain Arm is to the south. According to Wikipedia, Turnagain Arm was named by none other than William Bligh (think Mutiny on the Bounty), who was working for Captain James Cook at the time, looking for the Northwest Passage. They did not find it up either "arm" of Cook Inlet. After exploring the second "arm" and reaching the end, they had to "turn again". And there you have it.

Your initial reaction when you see these two pictures might very well be "there is no water...only mud". And you would be mostly right. There was lots and lots of mud, and just a little bit of water. The tide was out when I took these photos. Turnagain Arm has the largest tidal range of any body of water in the United States. The difference between low tide and high tide water levels here is about 30 feet.

Enough of the trivia. Here are my two pictures of Turnagain Arm. Remember - mostly cloudy pictures of mostly mud. I am sure I will find something more interesting to share in the coming days :-)

All I have for this post are a couple of mostly cloudy pictures of Turnagain Arm. Mostly cloudy was what we had every day, except for the last two, and maybe an hour or two here and there on the other days. No complaints here about the weather - you do not go to Alaska for warm, sunny, predictable weather - but it did pose some interesting photographic challenges.

Turnagain Arm is not an anatomical reference. It is a body of water. If you come up the south edge of the Alaska Peninsula, the Pacific Ocean transitions into the Gulf of Alaska which in turn transitions into Cook Inlet (with the Kenai Peninsula on your right and Anchorage to the north and east). When Cook Inlet gets to Anchorage, the waterway splits - Knik Arm continues to the north of Anchorage, while Turnagain Arm is to the south. According to Wikipedia, Turnagain Arm was named by none other than William Bligh (think Mutiny on the Bounty), who was working for Captain James Cook at the time, looking for the Northwest Passage. They did not find it up either "arm" of Cook Inlet. After exploring the second "arm" and reaching the end, they had to "turn again". And there you have it.

Your initial reaction when you see these two pictures might very well be "there is no water...only mud". And you would be mostly right. There was lots and lots of mud, and just a little bit of water. The tide was out when I took these photos. Turnagain Arm has the largest tidal range of any body of water in the United States. The difference between low tide and high tide water levels here is about 30 feet.

Enough of the trivia. Here are my two pictures of Turnagain Arm. Remember - mostly cloudy pictures of mostly mud. I am sure I will find something more interesting to share in the coming days :-)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)